Ishida Shoten

Craft Type: 13Edo Tsumami- Kanzashi

The craft of folding small pieces of silk and then gathering them together with the tsumami (pinching) technique is enjoying a small boom of popularity.

The hands-on experience classroom operated by Edo tsumami kanzashi (traditional Japanese hairpin) craftsman Tsuyoshi Ishida is always filled with several dozen people. The contents of the classes are aimed at beginners and remain the same every year, but there are certain people who wish to continue despite this and have been attending the classes for seven or eight years.

Many books explaining the tsumami (pinching) method have been published. The number of people who learn this as a hobby and the number of active creators is on the increase. Despite this, it is extremely difficult to master all of the processes involved, such as dyeing and cutting the silk. Because of this, many people tend to cut odd pieces of material they have laying around or purchase ready-cut habutae (thin silk fabric pieces) and start by learning the tsumami method.

The tsumami craftsmen who learned their trade under the guidance of a master craftsman currently number only about ten in total throughout both Kanto and Kansai plains. Although the production process is the same, the style of the end products differs between east and west. Whereas most of the items made in the Kanto area are used for shichigosan (festival celebrating the third, fifth and seventh birthdays of children), the Kansai area plays host to creators who specialize in making kanzashi for apprentice Maiko geishas, bunraku dolls and for theater productions.

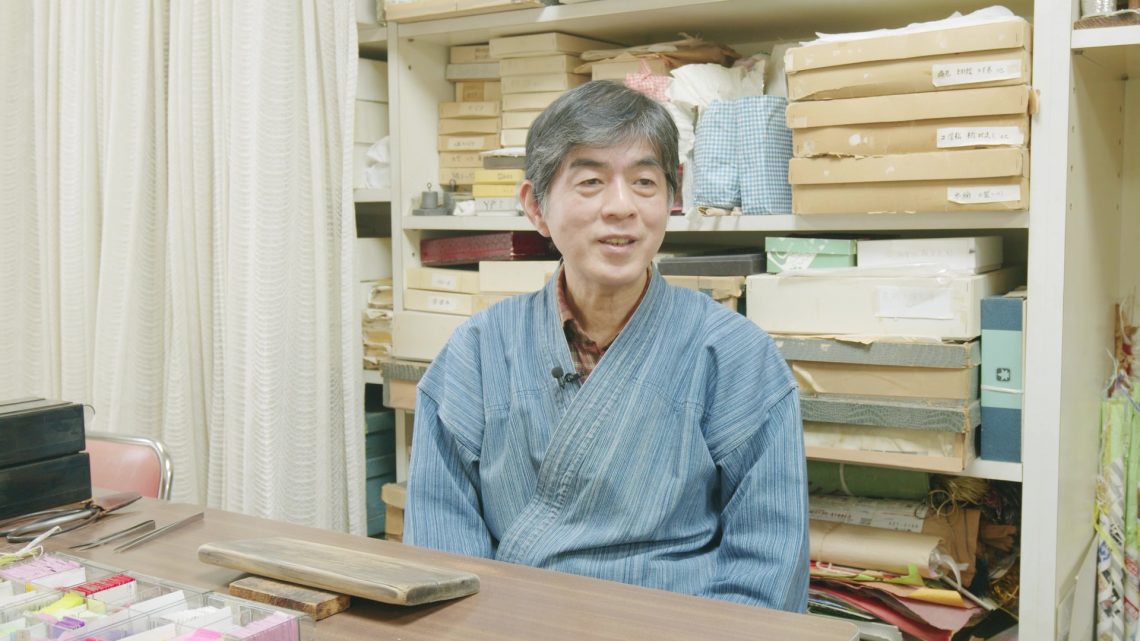

Ishida carried on in his father's footsteps immediately after graduating from school, and nearly forty years have passed since he first began to make tsumami kanzashi. He modestly states that he has continued in this work because he is unable to do anything else. His younger brother, who is also a tsumami craftsman, entered the trade after trying his hand at other work, and twenty years have now elapsed since then.

Most of his orders come from people who wish to coordinate the kanzashi with kimonos, and people who wish to wear them at events and ceremonies. Sometimes, he even receives orders from Maiko geishas who claim that all of the stores in Kyoto stock similar items and they want something that is different to what other people are wearing. And, approximately once every ten years, he receives an order from somebody who wishes to coordinate a kanzashi with western clothes.

Ishida asks all customers to describe what they want, and then forms an image in his mind that he draws on for inspiration. He says that once he has formulated an image of what to make, everything else falls into place. He creates the item based on this image initially, and then corrects it if it is wrong before completing it.

He first considers the design, then prepares all of the materials before creating and completing the order. Being the only person involved in all of the required processes in most cases is one of the features of tsumami kanzashi. Small elaborate changes here and there enables a wide range of different shapes to be created, and this is one of the fun parts of the entire process.

"The most attractive part of my job is having the freedom to create what I want. Although it is my job, there are also times when I feel that it is my hobby."

Saying this, the craftsman's cheeks suddenly pucker up in a gentle smile.

Craftsman Profile

| Craftsman Name | Ishida Shoten |

|---|---|

| Address | 4-23-28-401, takadanobaba, shinjuku-ku, tokyo 169-0075 |

| TEL | +81-3-3361-3083 |

| Representative | Takeshi Ishida |

| Website | https://kanzashi.org/ |

Craftsmen Specializing in 13Edo Tsumami- Kanzashi