“A sense of searing power within tranquility”

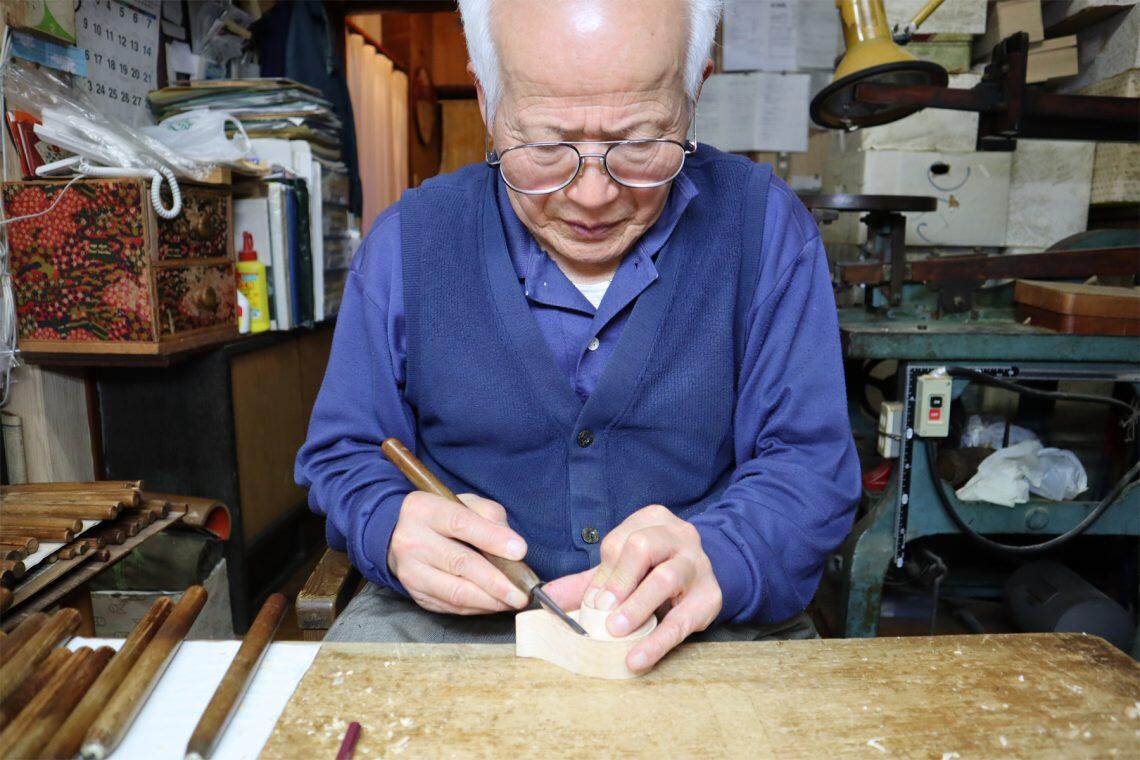

Kitazawa Wood Carving

Craft Type: 27Edo Moku-Chokoku

So, in the above paraphrase, related Richard Emmert, an artistic director of noh theater, master of the Kita School and authority on noh drama, in appraising masks made by Kitazawa Hideta.

Noh masks are carved with fine detail to embody them with textured nuance that enables noh actors to distill the required expressions when facing each other. Yet, at the same time, it is important that they project strong shadows when seen from distant audience seats. Thus, the strong shadows seen on a mask when an actor looks down are known as "kugumoru", or "clouding". Yet, if the carving has been too gentle or rounded in trying to achieve that effect, it does not matter how elaborate and detailed the carving is, the looked-for expression will not appear through the shadow.

Thus, above all, the mask carver must stay alert to the fact that masks are stage props that must work where they are used - thus, when mask props are for a new English production of noh, I take care to carve the masks to suit those western surrounds, which are mostly western theaters and halls, not dedicated noh theaters.

Likewise, traditional adornments for temples and shrines are chiefly carved with erect chisel incisions.

Such a chiseling technique is unheard of in western sculpting and is regarded as being unique when I take such pieces overseas. For instance, if I carve the mane of a decorative shishi (lion) with softly accented curls, they will lack prominence in the lofty spots such sculptures are used to adorn temples and shrines, so I must sink my chisels in firmly and vertically to produce shadow and light.

As a versatile woodcarver of Shinto and Buddhist deities as well as noh masks, Kitazawa Hideta uses heavy hardwood zelkova to maintain the exquisite wood grains amidst the inclement elements of wind and rain of his temple and shrine decorations but light Japanese cypress, which easily accommodates coatings, on noh masks. Carving hard zelkova leaves chisels ragged with wear, so I must sharpen them before use on Japanese cypress, which means that in 20 or 30 years of use my chisels are honed down to their bases.

I use some 250 chisels of various widths and shapes, changing from one to another depending on the touch needed. As I have memorized the blade widths and curvatures, I only have to touch a handle to know immediately that I have the chisel I need, remaining focused on the piece before me, not even shifting my eyeline for a moment from my creation as I carve and carve.

As the eldest son of Ikkyo Kitazawa, who carved the mikoshi (portable shrine) at Tomioka Hachimangu Shrine, the lion heads at Naritasan Shinsho-ji Temple and the family Buddhist altar for the late Ishihara Yujiro, Hideta grew up among tools and the learning process of using chisels, so that, upon graduating from university, he studied under his father before apprenticing himself to the workshop of mask carver Ito Michihiko, from where he gained recognition for his skills as a mask carver by undertaking the carving of masks for the Nomura Mansai family, a kyogen ensemble.

<

Being able to sculpt wood as well as carve and paint masks, the Kitazawas are often asked to restore wood carvings from the Edo period (1603-1868). Needless to say, there is also an endless procession of requests from across the globe, including art museums, universities and other such places, to give lectures, practical demonstrations and workshops.

Thus, with a gentle smile on his face, the woodcarver concludes, "All the highly tense dealings with stage related people are such fun."

Craftsman Profile

| Craftsman Name | Kitazawa Wood Carving |

|---|---|

| Address | 4-11-22, mizumoto,katsushika-ku, tokyo 125-0032 |

| TEL | +81-3-3609-4191 |

| Representative | Shuta Kitazawa |

Craftsmen Specializing in 27Edo Moku-Chokoku